l-World Economics Review Blog

Posts are by authors of papers published in the RWER. Anyone may comment.

Capitalism’s growth problem

from David Ruccio

Contemporary capitalism has a big problem. And no one seems to be able to refute it.

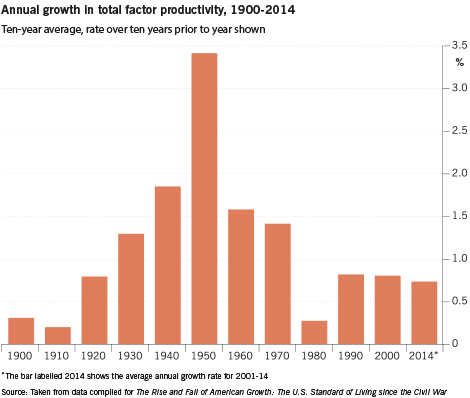

The problem, as Robert J. Gordon sees it, is that economic growth is slowing down, it has been for decades, and there’s no prospect for a resumption of fast economic growth in the foreseeable fure. After fifty (from 1920 to 1970) years of relatively fast growth, and a single decade (the 1950s) of spectacular growth, the prospects for continued growth seem to have dimmed after 1970.

In the century after the end of the Civil War, life in the United States changed beyond recognition. There was a revolution—an economic, rather than a political one—which freed people from an unremitting daily grind of manual labour and household drudgery and a life of darkness, isolation and early death. By the 1970s, many manual, outdoor jobs had been replaced by work in air-conditioned environments, housework was increasingly performed by machines, darkness was replaced by electric light, and isolation was replaced not only by travel, but also by colour television, which brought the world into the living room. Most importantly, a newborn infant could expect to live not to the age of 45, but to 72. This economic revolution was unique—and unrepeatable, because so many of its achievements could happen only once. . .Since 1970, economic growth has been dazzling and disappointing. This apparent paradox is resolved when we recognise that recent advances have mostly occurred in a narrow sphere of activity having to do with entertainment, communications and the collection and processing of information. For the rest of what humans care about—food, clothing, shelter, transportation, health and working conditions both inside and outside the home—progress has slowed since 1970, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

From what I have read, Gordon appears to privilege technical innovation over other factors (such as dispossessing noncapitalist producers and creating a large class of wage-laborers, concentrating them in factories and cities, and so on). He also seems to argue that the fruits of past economic growth were evenly distributed and that the drudgery of work itself has been eliminated.

Still, the idea that rapid economic growth took place during a relatively short period of time dispels one of the central myths of capitalism, much as the discovery that relative equality in the distribution of wealth and constant factor shares characterized an exceptional phase of capitalism.

And that’s a problem: the presume and promise of capitalism are that it “delivers the goods.” It did, for a while, and now it seems it can’t—which has mainstream commentators worried.

They’re worried that capitalism can no longer guarantee fast economic growth. And they’re worried, try as they might, that they can’t refute Gordon’s analysis. Not Paul Krugman or Larry Summers or, for that matter, Tyler Cowen.

All three applaud Gordon’s historical analysis. And all three desperately want to argue he’s wrong looking forward. But they can’t.

The best they can come up with is the idea that the future is uncertain. Thus, as Cowen writes, “many past advances came as complete surprises.”

Although the advents of automobiles, spaceships, and robots were widely anticipated, few foretold the arrival of x-rays, radio, lasers, superconductors, nuclear energy, quantum mechanics, or transistors. No one knows what the transistor of the future will be, but we should be careful not to infer too much from our own limited imaginations.

Indeed. We certainly don’t know what lies ahead. But, since the 1970s, we’ve witnessed growing inequality in the distribution of income and wealth, which resulted in and in turn was exacerbated by the most severe economic crisis since the 1930s. Capitalism’s legitimacy, based on “just deserts” and economic stability, was already being called into question. Decades of slow economic growth and the real possibility that that trend might continue for the foreseeable future mean that capitalism (not to mention those who spend their time celebrating capitalism’s successes and failing to imagine alternatives) has an even bigger problem.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário